Why Inflation Feels Different for Everyone — and Why Lower-Income Households Feel It More

Inflation is often discussed as a single number, but for most households, the real experience of rising prices feels far more personal. While official data may suggest inflation is cooling, many Americans still feel squeezed — and for good reason. The reality is that inflation does not affect everyone equally, and income level plays a major role in determining how painful price increases feel.

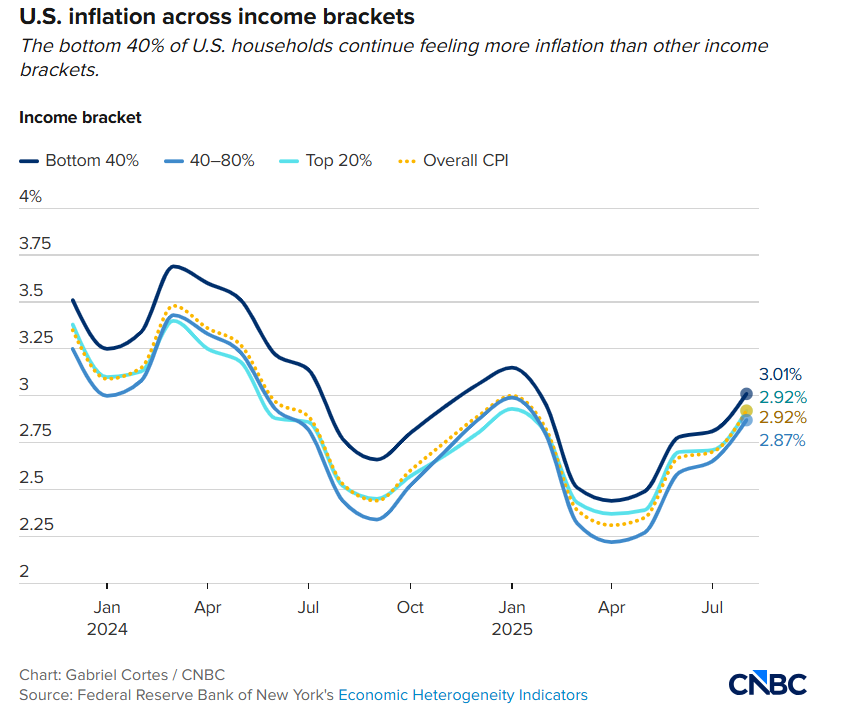

According to the latest data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, consumer prices rose 2.7% year over year in November. Although that figure came in slightly lower than expected, it remains above the Federal Reserve’s long-term target. More importantly, the headline number masks sharp differences in how inflation impacts households depending on how they earn and spend their money.

Personal Inflation Depends on What You Buy

Inflation is calculated using a broad “basket” of goods and services meant to represent average consumer spending. But no household spends like the average consumer. Families allocate their income differently depending on necessities, lifestyle, location, and income level — and those differences can significantly change how inflation is felt.

Lower-income households tend to spend a much larger share of their income on essentials such as housing, food, transportation, and utilities. These categories have seen some of the most persistent and stubborn price increases in recent years. In contrast, higher-income households devote more spending to discretionary services like travel, entertainment, and dining out, which tend to fluctuate differently and can sometimes be delayed or reduced.

Data analyzed by the Bank of America Institute shows that lower-income households experienced inflation closer to 3% on a year-over-year basis, slightly higher than middle- and higher-income households. While the numerical difference may seem small, the real-world impact is substantial when budgets are already tight.

Why Lower-Income Households Have Fewer Options

One of the biggest challenges facing lower-income families during inflationary periods is limited flexibility. When prices rise, higher-income households can often adjust by delaying purchases, switching brands, or cutting back on nonessential spending. Lower-income households, however, have far less room to maneuver.

Rent is a prime example. Housing costs have risen faster than overall inflation, and renters have limited ability to “shop around” once a lease is signed. Unlike discretionary expenses, rent cannot easily be reduced or postponed, and it often consumes a disproportionate share of income for lower earners.

Food and transportation present similar challenges. Grocery prices may fluctuate, but families still need to eat. Transportation costs are unavoidable for commuting to work, school, or childcare. As a result, lower-income households are often forced to absorb higher prices rather than adjust spending patterns.

Economists note that this inability to quickly scale back essential consumption magnifies the stress of inflation and leaves households more financially vulnerable.

Credit Use Widens the Financial Gap

How households manage rising costs also differs by income level, and credit access plays a significant role. Higher-income consumers are more likely to use credit cards strategically, paying balances in full and benefiting from rewards, cash-back programs, or travel points. For them, short-term borrowing may come with minimal or no interest costs.

Lower-income households, on the other hand, are more likely to carry revolving credit card balances. With average interest rates hovering around 20%, inflation-driven spending increases can quickly turn into expensive debt. As prices rise, these households may rely more heavily on credit simply to cover necessities, compounding financial strain over time.

This dynamic creates a feedback loop where inflation not only raises costs but also accelerates debt accumulation for those least able to afford it.

Inflation Expectations and Consumer Behavior

Despite persistent inflation concerns, consumer spending has remained resilient. Even as confidence surveys show widespread pessimism, many households continue spending — particularly during peak periods like the holiday season. Much of that spending is supported by credit rather than rising incomes.

Surveys suggest growing anxiety about the future. Roughly one-third of Americans believe their personal finances will worsen in the coming year, marking the highest level of pessimism in several years. Financial stress is especially pronounced among lower-income households, who face the greatest risk if inflation remains elevated or if an economic downturn occurs.

Economists warn that this growing divide reflects a broader “K-shaped” economic recovery, where higher-income households recover and stabilize faster while lower-income households fall further behind. Over time, this imbalance can weaken overall economic resilience.

Why the Inflation Gap Matters

Understanding why inflation feels worse for some households than others is crucial for both policymakers and consumers. A single inflation number does not capture lived experience, particularly for families whose budgets are dominated by necessities.

As inflation continues to evolve, its unequal impact highlights the importance of targeted economic policies, wage growth, and access to affordable housing and credit. Without those supports, even modest price increases can have outsized consequences for millions of households.

Inflation may be easing on paper, but for many Americans — especially those at the lower end of the income scale — the pressure remains very real.